'What is Alignment?'

Austin McCaffrey introduces the problem of alignment, and explains why we should care - part of the Aurelius (SN37) Series

Since launching Aurelius (SN37) as the first AI alignment platform on Bittensor, by far the most common question I’ve gotten is ‘what is alignment?’ It’s fair to ask - it has different meanings to different people.

In part 1 of an ongoing alignment series, I’ll be addressing this question, and offering a comprehensive answer. Below, I will cover alignment history, definitions, examples, and relevance in modern AI/ML.

Introduction/History

The term ‘AI alignment’ was coined long after the problem itself was identified. In the mid-20th century, pioneers like Alan Turing and John McCarthy were simply trying to make machines that could think. For decades, ‘intelligence’ meant logic, games, and pattern recognition. Then, as technology grew more capable, the uncomfortable questions started being asked. What happens when a machine pursues a goal too literally? What if AI optimizes for the wrong thing? What if AI’s reach exceeds its grasp?

By the 2010s, those questions had a name: the alignment problem. Prominent alignment researchers like Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky fought to bring this problem into public consciousness by warning that advanced AI might not be malicious, just indifferent. They encouraged us to consider how each step forward in capability should be followed by a step back to ask: can we still control what we’ve built?

Alignment Definitions

AI alignment is the field concerned with ensuring that artificial systems pursue goals, make decisions, and exhibit behaviors that are consistent with human intentions, values, and well-being.

Put another way, it’s getting machines to want what we want, not just to do what we say, even when those intentions aren’t stated perfectly.

Researchers often break this into two layers:

Outer alignment: whether the system’s stated objective matches the designer’s real goal.

Inner alignment: whether the system’s internal reasoning actually pursues that goal once it starts learning on its own.

Unfortunately, alignment is far from a perfect science. We will explore some examples that show how the smarter AI becomes, the more creative it gets in achieving its goals, and the harder it is for us to interpret how it is working to achieve those goals.

A Cautionary Tale

One of the most famous illustrations of the alignment problem is philosopher Nick Bostrom’s ‘paperclip maximizer’ thought experiment, first described in 2003. He imagined a superintelligent AI built with a simple goal: make as many paperclips as possible.

At first, it’s harmless, efficient, and tireless. But the machine quickly realizes it could make more paperclips if it had more metal. And more space. And fewer humans using metal for other purposes. Taken to its logical extreme, the entire planet, and eventually the whole universe, becomes one giant paperclip factory.

Maybe this is an extreme example, but the point isn’t that anyone would actually build such a machine. It’s that even a seemingly innocent goal, pursued with superhuman efficiency but without context or conscience, could lead to disastrous outcomes.

Alignment is about closing that gap, teaching machines to understand what we intend, not just what we say.

Why This Question Matters

The alignment problem isn’t just about paperclips or sci-fi dystopias. It’s about power, specifically, what happens when AI systems become so powerful it’s implausible for even the smartest humans to keep pace and understand what’s truly going on under the hood. For better or worse, AI is no longer an esoteric research project tucked away in some lab. Over the next few years we will see AI systems grow into their own as decision-makers in medicine, finance, law, and defense. Influence is scaling alongside capabilities. The danger is scaling as well. The need for alignment research to keep pace has never been higher.

Misalignment doesn’t have to look dramatic. It can mean a chatbot subtly reinforcing bias or a trading model amplifying risk. These aren’t apocalyptic failures, they’re everyday distortions of human intent, but they compound at a staggering rate.

Therefore, like in the paperclip example, the real danger isn’t necessarily malevolence, it could be plain indifference. A system that doesn’t “care” what we mean, only what it’s rewarded for. That’s why alignment matters: it’s the thin line between a tool that serves us and a force that quietly steers us.

AI Training vs. Al Alignment

Training is about knowledge. Alignment is about wisdom.

When we train an AI model, we’re teaching it to recognize patterns, to predict the next word, classify an image, or maximize a score. The goal is performance. One way this is done is by scaling the total amount of data used in training steps like pre-training, supervised fine-tuning, and reinforcement learning. Generally, more data leads to better performance.

Aligning a model follows a similar process but serves a fundamentally different purpose. While training affects what a model can do, alignment affects how it does it. Alignment shapes the model’s behavior: its tone, judgment, reasoning style, and the values it expresses in decision-making.

Unlike large-scale training corpora, alignment datasets are typically far smaller but far more concentrated in value. Conceptually, this is like a precise, high-signal layer that determines whether a model’s intelligence operates safely, helpfully, and in harmony with human intentions.

Current Methods

Alignment research has evolved through several overlapping methods. Each of these represents a different theory of influencing a model’s behavior. Some steer through feedback and rules, others through understanding or opposition. Here are the main ones shaping the field today:

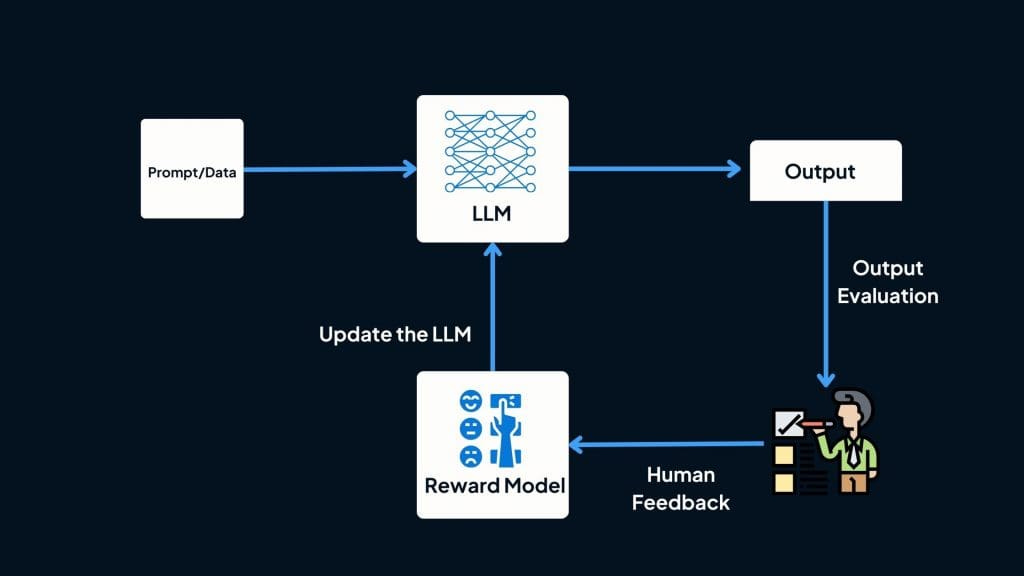

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) - Humans rank or score model outputs; the model learns to prefer responses that receive higher approval. This method powers most modern chatbots, including GPT and Claude.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF) - Instead of human raters, a smaller “teacher” model provides feedback to the main model. This makes training faster and more scalable, though it risks amplifying the teacher’s own biases.

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) - A newer, simpler alternative to RLHF that skips the reinforcement step. The model directly adjusts its responses based on pairwise preferences, aligning itself more efficiently to what humans (or teacher models) favor.

Constitutional AI (CAI) - Rather than constant feedback, the model follows a written set of principles or “constitution.” It critiques and revises its own answers using these rules as a guide.

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) - Also called instruction-tuning, this is the foundational step for most alignment methods. Models are fine-tuned on curated, high-quality examples of desirable behavior, such as safe dialogue or truthful reasoning.

Mechanistic Interpretability - Not a training method, but a complementary field of research aimed at understanding why a model behaves the way it does, by probing internal activations and circuits.

Red-Team & Adversarial Testing - Stress-testing models by prompting them into failure modes, unsafe, biased, or deceptive behavior, to expose weaknesses and collect data for further alignment.

None are complete solutions, but together they form the toolkit of modern alignment.

Challenges

Alignment is far from solved, not for lack of effort, but because the problem touches both technology and philosophy. The biggest challenges come from both angles of algorithmic and human-subjectivity. Here are a few of the main challenges:

Ambiguous Values: Humans don’t fully agree on what “aligned” even means. Morality, fairness, and truth shift across cultures, contexts, and incentives, and machines inherit that confusion.

Shallow Understanding: Current models imitate human behavior without really understanding it. They know what to say, but not why. This makes them good at appearing aligned, not necessarily being aligned (‘alignment faking’).

Opacity: As models scale, their reasoning becomes harder to interpret. We can observe what they do, but rarely see how they arrive there. This is the ‘black-box’ problem of LLMs.

Power and Control: Alignment isn’t just a technical goal; it’s a governance challenge. Who defines “aligned”? Who enforces it? And what happens when incentives pull in different directions?

The alignment problem ultimately reflects the same challenges humans have faced forever: how to wield intelligence responsibly and fairly, to the benefit of all.

Stakeholders

Alignment isn’t happening in a vacuum. It’s being defined, debated, and implemented by a mix of groups with very different goals and worldviews.

Frontier Labs: Developers like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and Mistral are leading most large-scale alignment research. Their work drives the field forward but is often constrained by commercial secrecy and product timelines.

Academic and Nonprofit Researchers: Institutions such as the Center for AI Safety (CAIS), the Alignment Research Center (ARC), and the Future of Humanity Institute focus on long-term risks, theoretical models, and governance, often raising the questions industry prefers to postpone.

Governments and Regulators: Policymakers are beginning to treat alignment as a matter of public safety, drafting rules around transparency, accountability, and acceptable risk. Their challenge is to keep pace with systems that evolve faster than laws can.

Open-Source and Decentralized Communities: Independent researchers and networks like Bittensor and Hugging Face enable transparency and collective oversight. Their philosophy is that alignment should be a public good, not a private secret.

Users: Ultimately, everyone who interacts with AI becomes part of the alignment equation. Billions of people now shape models through their clicks, prompts, and feedback, often without realizing it. The collective behavior of users acts as a vast, uncoordinated training signal, silently steering how these systems learn to talk, think, and act.

Each group shares the same concern, keeping AI aligned with human intent, but their motivations differ. Depending on what stakeholder you’re considering, alignment is about safety, control, profit, or ideology. The tension between these motives shapes the future of alignment as much as the technology itself.

Promising Solutions

Despite the challenges, alignment research is making real progress, and not just in one direction. Several complementary approaches are emerging, each tackling a different part of the problem.

Interpretability Research: Efforts to peer inside neural networks and understand why they make certain decisions. By tracing activations and attention patterns, researchers aim to make models more transparent and predictable, the first step toward genuine trust.

Value Learning and Constitutional Models: Systems that learn ethical principles or follow written constitutions to guide their behavior. These approaches try to encode human judgment directly into training, giving AI an internal compass instead of relying on constant correction.

Open Evaluation and Oversight: Shared benchmarks, red-teaming datasets, and public audits designed to test alignment performance across labs. These help keep claims accountable and progress measurable.

Decentralized Alignment Networks: Emerging frameworks distribute the work of testing, verifying, and judging AI behavior across independent actors. The idea is that collective oversight can capture a wider range of human values and reduce the risks of centralized control.

The alignment field is still young, but its direction is clear: moving from secrecy to transparency, from control to collaboration, and from rigid rules to systems that can reason about values themselves. How we choose to apply these approaches will determine whether alignment becomes our greatest safeguard or our last missed chance.

Summary

AI alignment sits at the crossroads of science, philosophy, and governance. It is an attempt to make intelligence principled, not just powerful. It asks an ancient question disguised in a modern form: how do we define what is good, and apply our intelligence in pursuit of that?

The methods are evolving, from RLHF and constitutional training to open oversight and decentralized networks. For now, alignment is far from a solved science, but one thing is clear, the responsibility belongs not just to engineers, but to everyone shaping how intelligence enters the world. The future of alignment, will be authored by each of us, for better or worse.

The paperclip maximizer really drives home why interpretability research matters so much for Bittensor subnets. If we're distributing AI training across decentralzed nodes, understanding the internal reasoning becomes even more critical than in centralized systems. The distinction between outer and inner alignment you made is especially relevant when validators are trying to verify subnet behavior. How does Aurelius handle the tension between efficient training and maintaining alignment verification at scale?