How should a Subnet be scored? Crucible Labs and the art of assessment

As subnets grow in volume and diversity, the question of how to assess their performance becomes more complex - and more important.

Looking back on Bittensor’s 2024 at the year’s end, one metric stands out: in 12 months, the volume of Subnets 10x’d. From price prediction to deepfake detection, data scraping to protein folding, the range of capabilities has expanded in tandem.

For Bittensor users, this diversification is hugely welcome. But for validators, miners, and investors, it carries a complex question: how can such varied subnets be meaningfully compared, assessed, and ranked? The consequences of how we assess subnets reach beyond the financial. It also influences how subnet builders shape their network, allocate resources, and direct the future of the whole ecosystem.

Crucible Labs, who launched a rapidly-scaling validator in October 2024, recently released their answer to the question of how they allocate emissions. Their assessment criteria are divided into three key categories: product, team, and market.

The fact that Crucible Labs can even gauge these criteria demonstrates progress: it suggests that subnets are now professionalising to such an extent that their investability (or lack thereof) is becoming increasingly evident across a number of indicators. Together, these categories give Crucible Labs an emergent picture of the likelihood of a given subnet’s future success.

In turn, Crucible Labs use these categories to score subnets into three levels of investability: Premier Subnets, equivalent to Series A allocation, is the highest; Emerging Subnets are seed stage, and Seedling Subnets are pre-seed.

Three of Crucible Labs’ top five Premier-category subnets are operated by Macrocosmos. While this is welcome, it also invites us to take a closer look at how subnets can be meaningfully compared and analysed - and what the macro trends reveal about the general progress of the Bittensor ecosystem.

Product, team, market

An X post, some hype, and a landing page: many subnets, some of which are now among the very best, started with little more than this.

For validators, investors, and users, this represents a problem. Should they be supportive, or sceptical? Where can they turn for additional information? And if none is forthcoming, how can they go beyond the official announcements to accurately gauge what’s actually going on?

Product - the fundamentals of a subnet’s design - is where to start. However, for many subnets this is difficult to ascertain. Crucible Labs list a range of potential indicators, from GitHub repositories to comprehensive whitepapers.

They also list ‘Properly designed and robust incentive mechanisms,’ but even a strong grasp of the rudiments of machine learning is not always enough to provide a comparative analysis between two very different subnets.

Moreover, exceptional design, rigorous documentation, and deep GitHub repositories are not in and of themselves guarantors of success. Market matters, too. Engineers, especially in the early days, pushed ahead with subnet concepts that were interesting in and of themselves, but lacked a clear route to market. In the time when the total number of subnets fell below two dozen, this wasn’t an immediate problem. In a time of 60-plus subnets, it’s existential. Crucible Labs cite adding value to the Bittensor ecosystem, addressing advances in AI research, and targeting a substantial opportunity in the broader market as signs of strong marketability.

But even these two categories of subnet success are insufficient without a third: team. The experience, accomplishments, and pedigree of the founders and their core team are critical. In addition, their engagement with their community and the velocity of their releases help to prove their commitment, turning promises into practice. When product, market, and team are properly aligned, progress intensifies - and potential is realised.

Subnet trajectories

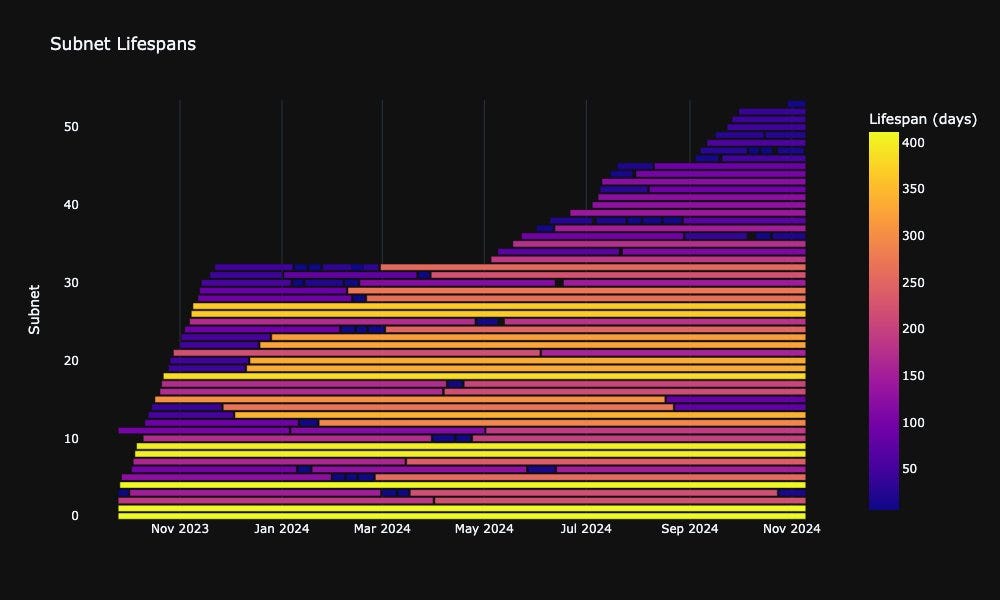

Our own research suggests that subnet lifespans are lengthening. As more and more subnets reach maturity, standards of quality and professionalism should increase - which should increase competition, driving standards still higher. Moreover, maturity also provides another avenue through which to gauge performance.

The potential of nascent subnets are, by their nature, hard to calibrate: with so many variables, uncertainties, and risks, a strong concept with promise of future impact is in itself a poor indicator of investability.

However, as subnets reach maturity, their ability to deliver on their promises becomes much clearer. Do they have a product? Is it marketable? How are users engaging with it?

The logic of subnet expansion means that no subnet can afford to stand still. The tokenomics of Tao suggest that subnets will have to compete for the same emissions; at 60 subnets, capturing a sizeable enough share to maintain growth is reasonable; at 600 subnets, it’s implausible.

Therefore, subnets must monetize their networks and build revenue channels beyond emissions - in other words, they must offer products and services that people actually want. But the challenge is steeper than this would suggest.

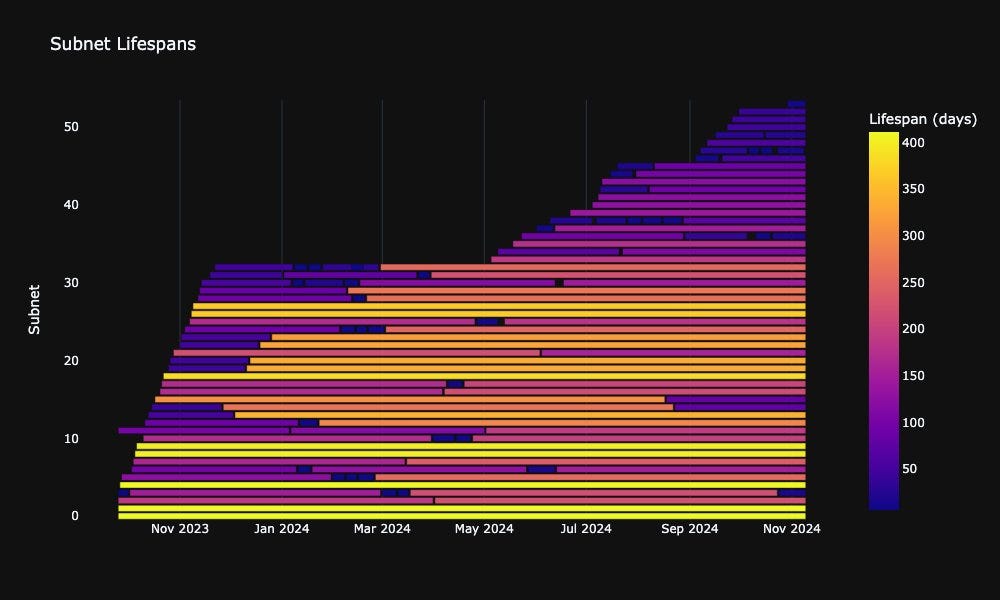

To understand the likely trajectories of subnets, we need to know more than just their average lifespan - we need to know how well they can secure emissions. Plotting expected emissions for subnets, based on data from around 150 subnets, reveals the vast gulf between successful and unsuccessful subnets. The mean line, tracing the average emissions (and therefore the most likely path your subnet will follow), disguises a lot of variability.

While the bottom 10% of subnets (represented by the red line) take 3 months to reach 0.5%, the top 10% of subnets (green line) have reached 4% within a single month. And this inequality is not just at the extremes. We see it again in the stark differences between the top 25% and bottom 75%.

Like the winner-takes-all miner competitions within subnets, the competition between subnets displays the same disparities - which drives relentless improvement. As more subnets compete in Bittensor the emissions pool is further diluted, forcing teams to work hard to sustain their emissions. Stark reward distribution means that only the best can survive - because the rewards at the bottom are so low, subnets that fail to compel support and convene resources are weeded out.

This ensures that the ecosystem continues to grow towards the efficient, the competitive, and the effective. Which means that, if you’re serious about running a subnet, you need to be resilient, committed, and fully focused in order to reach exit velocity and sustainability.

That's why we agree with Crucible Labs that product, team and market should be core components of any subnet scoring system. Without strong indicators across these three categories, it’s unlikely that a subnet will be able to build a viable monetization strategy - and without such a strategy, surviving in a competitive low-emission future is almost impossible. These are, after all, the fundamentals underlying all good business investment. They represent the foundations of trillion-dollar industries worldwide.

The advent of subnet assessment criteria, and the professionalised emissions allocation it enables, is a small but significant sign that Bittensor is maturing - fast. Great news for the ecosystem - and added incentive for subnet owners like Macrocosmos to maintain a relentless focus on continuous improvement.

From 2025, we'll be publishing a series of features on how to operate an efficient subnet and incentive mechanism, and on broadening the evaluation heuristics when we design our own systems. Subscribe below to receive each article as it’s released.